Blog

Silicon Valley Is Back In Cleantech. Will This Time Be Different?

Wal van Lierop

Jul 6, 2021

Previously published on Forbes.com

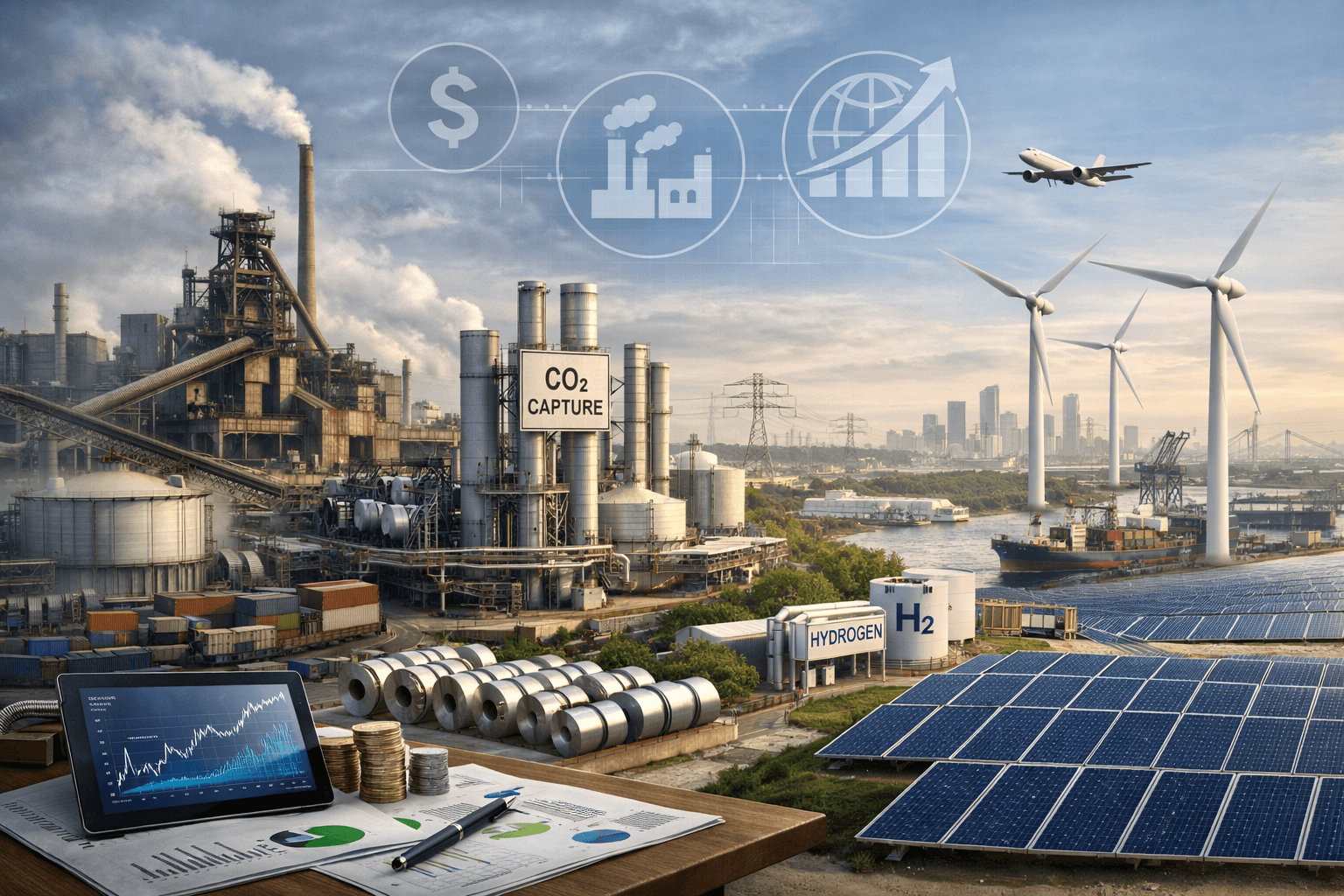

In the early 2000s, Silicon Valley funded cleantech with little understanding of the traditional industries that were supposed to want its innovations. After losing billions of dollars, major Silicon Valley VCs decided that cleantech and VC must be incompatible—until the recent flood of easy ESG and impact capital changed their minds.

In 2020, investors piled a record $17 billion into 1,009 cleantech firms. But there is chatter about whether cleantech VC will work “this time.”

The cleantech resurgence is vital because the world does not yet have the technologies to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Today’s cleantech investments will determine whether climate change can be limited to 2° C above preindustrial levels—the point beyond which the risks become more severe and unpredictable.

So why did cleantech venture capital (VC) collapse in the 2010s, and will “cleantech 2.0” turn out better?

New Shiny, Object

When I started investing in cleantech in 2001, Silicon Valley needed a new bright, shiny object in the wake of the Dotcom Bubble. Solar, biofuels and hydrogen fuel cell technology began to garner attention. But “cleantech” didn’t really exist. We joked that people thought it was a new dry-cleaning technology.

All that changed when Vice President Al Gore premiered An Inconvenient Truth in 2006. A year later, Kleiner Perkins chief John Doer announced his firm’s push into cleantech during a tearful TED Talk. His firm then made Al Gore a partner. Capital flowed into cleantech, soon boosted by the Obama Administration’s pro-cleantech policies.

Over the next five years, a slew of cleantech darlings went bust. Most famously, Solyndra, a solar startup, filed for bankruptcy in 2011 despite having received $535 million in U.S. government-backed loans. In 2013, Reuters went so far as to claim that “cleantech tarnished Kleiner and VC star John Doerr.” Cleantech had become a dirty word in Silicon Valley.

The Conventional Narrative

Cleantech was supposed to be “the next big thing.” Instead, VC investors lost over half of the $25 billion they invested in cleantech between 2006 and 2011 according to researchers at MIT, who titled their paper: “Venture Capital and Cleantech: The Wrong Model for Clean Energy Innovation.”

This paper became the definitive (i.e., much cited) account of what went wrong. It argued that cleantech VC is problematic for a few reasons. First, the investment cycle is significantly longer than the three to five years VCs prefer. Second, innovations based on science and engineering, versus software, are too expensive and time-consuming to develop and test. Third, there is “no room for error” because traditional industries operate in commodity markets with “razor-thin margins.” Very true.

Put differently, cleantech VC failed because Silicon Valley couldn’t “move fast and break things” in new markets, as Facebook’s now retired motto recommended. The researchers also concluded that the cleantech sector “… suffers especially from a dearth of large corporations willing to invest in innovation.” Why could that be?

Don’t Worry, We’re from the Internet

During my two decades in cleantech VC, I’ve had the privilege to learn from scientists, engineers and executives who work inside traditional industries. I’m talking about oil and gas, cement, electric power, mining, metals, petrochemicals, shipping and others that enable the wonders of modern life (and fuel climate change).

From their perspective, Silicon Valley failed at cleantech VC not for a lack of ingenuity, but a lack of empathy and awareness. In their eyes, Silicon Valley showed up around 2007 and effectively said, “Hi, Al Gore tells us you’re killing the planet. But don’t worry. We, the people who fund innovative ways to take pictures of your own face and share it with friends, are here to help.”

But rather than offer solutions for specific industry problems, Silicon Valley too often hypothesized quick fixes for climate change without having studied the system impact and effectiveness of their suggestions. Ideologically driven and in search of quick returns, this approach to cleantech was ill-equipped for traditional industries that, in some cases, literally keep the lights on.

Though willing to innovate, these industries could not afford to be guinea pigs. Cleantech startups of this era struggled to complete satisfactory testing and development let alone penetrate a market at scale (Tesla being the notable exception).

The Path to Returns

Once again, the market is crowded with new cleantech VCs and funds promising that Silicon Valley can save humanity from climate change. It feels like the early 2000s all over again. Will things turn out better this time?

Hopefully. There is nothing inherently incompatible about cleantech and venture capital. There is no reason why cleantech funds cannot achieve an internal rate of return (IRR) above 20%. There is, however, incompatibility between industrial firms struggling to adapt to a net-zero future and Silicon Valley-ites who come to the rescue with too much hubris.

VCs must aim to partner with rather than preach to industrial firms. The infrastructure in traditional industries is extremely expensive to change or replace and can create value for decades. Industrial businesses are highly regulated because unlike smartphone games, steel plants face restrictions around zoning, safety, waste disposal and more. They might have one shot at using their cash reserves to future-proof their businesses and survive the energy transition.

That does not excuse industrial firms from taking responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions or other forms of pollution. The point is to approach cleantech VC with humility and a willingness to learn. Stop trying to solve climate change and start solving business problems that make fossil fuels hard to dislodge. There is immense knowledge, value and innovation potential within traditional industries.