Blog

The Ecosystem Model Part II: Getting Innovation Past Corporate Antibodies

Wal van Lierop

Oct 23, 2018

As published on Forbes.com

Innovation in the industrial world is opaque to most of the billions of people who depend on energy, mining, forestry and manufacturing companies for many aspects of their daily life. I’d like to take you behind the scenes of industrial innovation.

The way Silicon Valley startups pump out mobile apps is nothing like the complex, capital-intensive innovation process in the industrial world. How resource-intensive industries innovate – or not – affects whether our societies can address systemic global problems like inequality, public health, biodiversity and carbon emissions.

I can offer the following back-stage view into industrial innovation because my company Chrysalix works with many companies involved and we have been in this space for two decades. In July, the Canadian mining company Teck Resources Limited (a recent investor in Chrysalix) announced that its “autonomous haulage pilot” at Highland Valley Copper would have six trucks on line by the end of 2018. It would be the first autonomous fleet in a deep pit mine and potentially save $20 million annually at its Highland Valley Copper operation. Teck said it had also tested a “shovel-based ore sorting technology” and planned to “…fully operationalize the technology with installations on the rest of the main shovel fleet.”

Both advancements come from outside Teck. The autonomous haulage trucks are made by Caterpillar, which partnered with a self-driving vehicle startup called Torc Robotics to develop the machinery. The “shovel-based ore sorting technology” comes from the startup MineSense (in which Chrysalix is an investor). It sorts ore from waste rock at the point of extraction, meaning that waste rock doesn’t need to be transported to a mill where it would be crushed, processed and then sorted. That change can save tens of millions of dollars and reduce the burning of diesel fuel and use of water.

Teck’s implementation is notable because large industrials and small startups have radically different cultures. It’s the difference between steering a cruise ship and driving a speed boat. We often celebrate the nimble speed boat while chastising the cumbersome cruise ship. Rarely do we acknowledge the cruise ship’s responsibility to thousands of passengers.

As I argued recently in Forbes, the world’s vital, uncelebrated industrial companies could become disruptors once again if they build ecosystems of startups to source breakthrough technologies – just as Caterpillar and Teck have done. However, for industrials to innovate like Silicon Valley and for startups to win over industrials, both need deeper awareness of each other’s mindsets. Moreover, they need a better strategy for getting innovations past ‘corporate antibodies.’

The corporate antibody

Industrials can make millions of dollars from tiny, cents-shaving inventions, but they likely can’t remain market leaders without step-change innovations.

In the consumer space, Kodak and Blockbuster exemplify this dilemma. Kodak is hanging on for dear life because it underestimated how cellphones would dominate digital photography. Blockbuster refused to adapt to on-demand video and streaming when it had a chance. Unlike the Titanic, these companies saw the iceberg in time but still didn’t change course.

Even if Kodak and Blockbuster had acquired breakthrough technologies, implementing them is harder than sourcing them. Big corporations develop corporate ‘antibodies’ that:

See only the downside of innovation risks, not the upsides.

Protect the jobs, power structures and processes of entrenched employees.

Resist divergent, weird people who spot icebergs and offer solutions (a.k.a., startup founders).

The antibodies feel threatened by outside innovations whether they’re threatening or not.

The perception of failure

The ecosystem model attempts to bypass the antibodies by uniting two entities – industrials and startups – that have different cultures. The hardest difference to reconcile is their approaches to failure.

Large industrials want ‘to be first to be second.’ They hope some other company will bet its brand reputation and customer relationships on a startup’s pilot program.

Conversely, startups gloat about failure. Give startup founders microphones, and you’ll hear the same clichés about “going all in,” “learning from failure” and “pivoting.” Failing is their coming-of-age ritual.

Translating between these cultures is awkward. In one case I worked on, an industrial had 60 people evaluate the startup over a two-year period. That cost as much as the startup spent to build a full-scale system pilot.

Overcoming the antibodies

Industrials can’t afford to fail publicly, but startups can’t afford not to run their pilots. Capital will run out eventually. How do you overcome this difference?

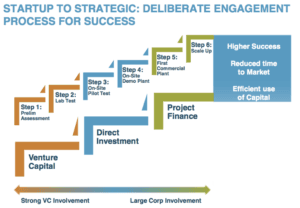

One solution is to make disruptive change feel incremental to the industrial, partly by sourcing it from a well-managed ecosystem and partly by injecting capital in defined stages. It looks like this:

Venture capitalists shoulder the risk of assessment and lab testing, where the failure rate is highest but capital requirements are lowest. Industrials invest directly in pilots and demo plants once vetting has mitigated some risk. Only after a proven pilot does the industrial commercialize and scale the innovation, sometimes through acquisition and sometimes by being a customer. These stages turn the wheel of the cruise ship cautiously without stifling the speed boat.

Teck’s announcement illustrates those stages. The term “autonomous haulage pilot” means that the autonomous trucks are in Step 3. Teck plans to “fully operationalize” the shovel technology, meaning it’s at Step 5 or 6. Over 100-year-old Teck is innovating, just not in the freewheeling way Silicon Valley celebrates.

Move calmly and get it right

Phased implementations are an enigma to the ‘move fast and break things’ ethos of consumer tech. But the notion that industrials could or should act like agile startups is misguided. Doing so could kill their core businesses. Likewise, startups that develop antibodies and resist change don’t last long.

A thriving innovation ecosystem needs speed boats and cruise ships. The ecosystem model works if these players are aware of each other’s cultural differences and prepared to deal with them. Behind the scenes, industrial firms are addressing carbon emissions and other environmental challenges through innovation. The process may be slower and riskier, but the outcomes can be world-changing.